Extreme Balloon Flights

The history of ballooning is an epic that spans centuries and continents and could fill its own library with tales of jubilant success and tragic failure. From the first experimental unmanned flights to today’s adventures to the edge of space, every unpowered ride in the sky offers its own unique challenge. In a balloon, perhaps more than any other vehicle, a pilot is at the mercy of the elements. These are the balloon flights that changed the world.

First Hydrogen Balloon – 1783

In 1662, Henry Cavendish’s poured acid on iron, discovering in the process “inflammable air,” a lighter-than-air element we know today as hydrogen. Almost 20 years later, a team of Frenchmen recreated Cavendish’s experiment on a grand scale, pouring barrels of sulphuric acid onto half a ton of scrap iron, and feeding the resultant hot and toxic gas into an airtight silk bag the size of an elephant. The bag took off, flying over Paris and crash landing 45 minutes later in the village of Gonesse, where the limp wreckage of the first ever hydrogen balloon was attacked by French hillbillies wielding pitchforks and knives. We wouldn’t make that up. It was an exciting start to a worldwide balloon race into the skies and across continents that continues today.

First Manned Balloon Flights – 1783

If it were up to King Louis XVI, criminals sentenced to the guillotine would be the first human passengers lifted into the skies (a sheep, rooster and duck rode a balloon a few months earlier). Paper-biz brothers, Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Etienne Montgolfier, however, took the flight into their own hands, climbing into the carriage of an ornately painted 75-foot tall balloon and taking to the skies powered by the hot air of a bonfire barbecue attached at the contraption’s base. The flying fire hazard worked, with the balloon reaching an altitude of 3,000 feet on November 21, 1783 before it landed charred but salvagable on the Butte-aux-Cailles nine miles away from the place of liftoff.

Just more than a week later, on December 1, 1783, Jacque Charles and the Robert brothers launched their own balloon in Paris — this one a more massive version of their earlier hydrogen powered balloon. The flight took them 1,800 feet high and 36 km far before landing. But after that inaugural trip, Charles hadn’t had enough. He kicked Nicolas-Louis out of the carriage and took the balloon himself above the clouds to a knee-clattering altitude of 9,000 feet, where he began suffering from a then-inexplicable earache. He gradually released hydrogen from the balloon and landed, never to fly again.

Farther and Crazier

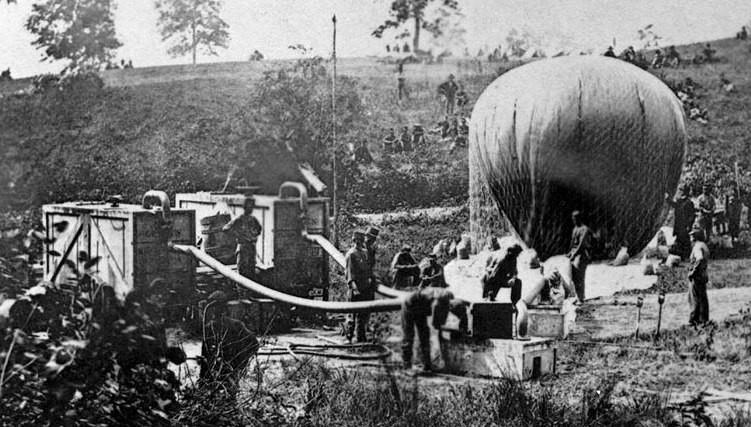

With the ascent of the first manned balloon, the age of ballooning — and the age of human flight — had begun. Before long, Jean-Pierre Blanchard floated across the English Channel, George Washington watched the first American manned balloon lift off over Philadelphia and the first aviation disaster occured in Tullamore, Ireland. A balloon crashed into a chimney causing a fire that destroyed nearly 100 houses. By the 1850s, here-to-there ballooning had grown commonplace, with throngs growing tired of watching man-blown bubbles take off and land. Enter Madame Poitevin, a pioneer of sorts who rode a horse attached to a balloon into the skies. When she tried to do the same with a bull, authorities cut her down and charged her with cruelty to animals. As unlikely a character in aviation history as Madame Poitevin may have been, the next innovation in ballooning — war balloons — may have been even more unexpected. During the American Civil War aviators sat in hydrogen balloons thousands of feet above battlegrounds, using signals to direct artillery upon enemy targets. The US Army uses balloons in warfare even today.

Higher and Higher

As balloon technology and knowledge of the atmospheric improved, men kept going skyward, often with deadly consequences. In the 1860s and 1870s, teams of men died or drifted back to earth deprived of oxygen and unconsious as they pushed to become the first to reach the stratosphere, which begins at about 30,000 feet. Finally, in 1901, Arthur Berson and Reinhard Süring got there and back — barely, with both blacking out en route to their peak altitude of 35,500 feet. Lucky for them, they came to as their balloon drifted into more hospitable altitudes, regaining their wits enough to control the balloon before it crashed to earth.

For the first time in the 150 year history of ballooning, the edge of the stratosphere, and higher, was seen as possible. But supplemental oxygen would afterwards be necessary for any flight above 10,000 feet, where pilots experience the first symptoms of hypoxia: lightheadedness, dizziness, blurry vision and euphoria. At 20,000 feet, it gets quickly worse, with balloon crews going unconscious in less than 15 minutes. At 30,000 feet, pilots have only about a minute without supplemental oxygen before the world goes dark.

Swiss physicist and inventor Auguste Piccard had an answer for the perils of ultra-high altitude: science. In 1932, the brilliant and brave madman built a pressurized cabin and attached it to an oversized balloon that would expand as atmospheric pressure gave way in the upper reaches of the sky. His innovations helped take him higher than anyone before, 52,498 feet.

Several crews followed his lead in the 30s, climbing to the middle reaches of the stratosphere, first 60,000 feet and then 70,000 feet. In 1934, a crew of Russians took a hydrogen balloon to a then record of 72,000 feet before their balloon broke up during descent, sending the men to their deaths. Still, their altitude record stood until the 50s, when the US Navy and Air Force sent ment to 96,784 feet and then 102,400 feet. In 1961, Navy Commander Malcolm D. Ross and Lieutenant Commander Victor A. Prather were strapped into a balloon and sent into the stratosphere to test the Navy’s new Mark IV full-pressure suit — a precursor to the suits that would be worn a year later by the Project Mercury astronauts. Ross and Prather reached an altitude of 113,740 feet, a balloon record that still holds half a century later.

Photo Credit: carolynconner / Flickr.com

Photo Credit: carolynconner / Flickr.com

Across Oceans and Around the World

As astronauts reached once-thought impossible heights in the 50s and 60s, a host of balloon pilots tried and failed to drift across the Atlantic and Pacific. The journey would demand favorable weather conditions and more than 100 hours in the air, with every second wearing on the structure of the balloon and each minute more dangerous than the last. Finally, in 1978, Ben Abruzzo, Max Anderson and Larry Newman flew the helium-filled Double Eagle II from Maine to France, setting a distance (3,107 miles) and endurance record (137 hours) and becoming the first men to fly a balloon across the Atlantic. 3 years later, the Pacific finally fell, with Abruzzo and team flying more than 5,000 miles from Nagashima, Japan to Covelo, California, a journey that took just over 84 hours.

The widest oceans conquered, there remained one main ballooning challenge unfulfilled: circumnavigating the globe. Innovations in weather forecasting and GPS finally made that possible in 1999 as Swiss doctor Bertrand Piccard, grandson of Auguste Piccard, and Brian Jones pulled off the impressive feat in 19 days, 21 hours, and 55 minutes. The trip took them high (more than 37,000 feet) and fast (up to 105 miles per hour at times) from Chateau-d’Oex, Switzerland to the Egyptian desert, a trip of more than 25,300 miles. In 2002, after failing five times, Steve Fossett circumnavigated the globe in a balloon all by himself.

What record is next?

Comments